Think Like a Missionary

Insights for Preaching and Culture from the World of Missiology.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should acknowledge that my missionary vocation and experience profoundly influence how I think about preaching and culture. I spent my teen years as a missionary kid in Central America. I have spent most of my adult life as a cross-cultural missionary as well. By default, I tend to think like a missionary.

“Thinking like a missionary” will kill any tendency to see culture as a monolithic beast to slay. For example, James Nieman and Thomas Rogers (Preaching to Every Pew: Cross-Cultural Strategies, Fortress Press, 2001) seek to equip preachers to address multicultural audiences by applying principles of missional anthropology. From this perspective, they describe culture in three ways:

First, culture is a process. Far from a stable force binding societies together, it is in constant flux.

Second, culture is plural. There is not one culture, but many. And each of the many cultures contains multiple cultural systems that influence and borrow from one another.

Third, culture is paradox, a place of struggle. Culture is usually not a consensus, but a variety of meanings competing with one another for predominance.

Culture as process, plural, and paradox precludes a single, one-size-fits-all approach. Cross-cultural missionaries spend years studying the language, customs, and worldview of a people group in order to craft an appropriate presentation of the gospel, and to cultivate a relevant church. Likewise, preachers in the North American (or any other) context must see the field with missionary eyes. We must exegete our culture as well as our text, and preach with cultural intentionality. This means contextualizing our message and envisioning the church that must be gathered for the Gospel to have a transforming impact in our setting.

The “Newbigen Gauntlet”

The world of missions has provided two provocative challenges in recent decades that have stimulated the conversation about the church and culture. The first is a missiological observation; the second is a theological reorientation.

The missiological observation came from an Anglican bishop, Lesslie Newbigin. He returned to England from a 38-year missionary career in India to discover that his home culture was as resistant to the gospel as any he had encountered elsewhere. In the mid-1980’s, he asked a question that launched a discussion that continues today. “What would be involved in a missionary encounter between the gospel and this whole way of perceiving, thinking, and living that we call ‘modern Western culture’?” (Foolishness to the Greeks: The Gospel and Western Culture, Eerdmans, 1986, p.1)

Previously, most thinking and writing about Christianity and culture in the western context had come from theologians, like Richard Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. Their insights were stimulating, but they did not have the experience of having tried to communicate the gospel cross-culturally. Newbigen believed the time had come to begin applying the insights of missionaries. He called for a missiology for western culture.

Numerous authors have picked up the “Newbigen Gauntlet” on both sides of the Atlantic, treating the West as a cross-cultural mission field. They have focused on the consequences of two major shifts in current western culture. First, the shift from a modern to a post-modern theory of knowledge has left us with the need for new approaches to communication and apologetics. Second, the shift from Christendom to post-Christendom has left the church in need of a new rationale for its life and work—or perhaps a return to its pre-Christendom way of being in the world. One of the dominant themes is the relationship between church and mission.

The “Missional” Movement

This leads to the theological reorientation that contemporary missiology brings to our discussion: that the church is, by nature, missionary. The church does not have a mission; God has a mission, and he sends the church unto the world to complete it. David Bosch may have articulated it best:

The church is not the sender but the one sent. Its mission … is not secondary to its being; the church exists in being sent and in building up itself for the sake of its mission. … Missionary activity is not so much the work of the church as simply the church at work… Since God is a missionary God, God’s people are a missionary people. (Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission, Orbis Books, 1991, p. 372)

This insight birthed the “missional church” movement. The term “missional,” seems to have become a buzzword so widely used as to become subject to the law of diminishing significance. Any outreach or service activity of the church, from door to door evangelism to cooking soup for the homeless is likely to be called “missional” these days. While these may well be a part of a missional church, they are not the parcel.

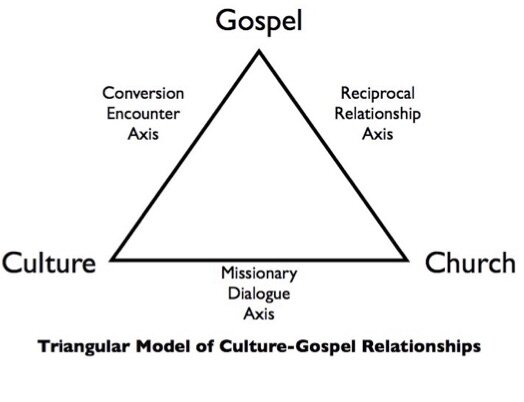

Newbigen and others have portrayed the missional process as a three-way conversation between the church, the gospel, and culture. Gospel dialogues with culture in a way that is both relevant and challenging. An ongoing conversation with the gospel continually transforms the church. And the church engages in a missionary encounter with culture as its new way of living in the world becomes the embodiment of the gospel. (See Lesslie Newbigin, The Open Secret: Sketches for a Missionary Theology, Eerdmans, 1978, p. 165-172 and George R. Hunsberger, Church Between Gospel and Culture: The Emerging Mission in North America, Grand Rapids, 1996, p. 8-10)

What Is “Missional Preaching”?

Is “missional preaching” evangelistic preaching? Or is it preaching that calls God’s people to missional engagement? Both are good ideas. Neither tells the whole story.

The goal of the missional church is much more than more evangelism, more community service, or more missionary activity. The goal is a radically renewed church culture. A church culture that is continually transformed by the gospel so that it becomes the relevant embodiment of the gospel to a broader culture that is then radically challenged by the gospel.

Missional preaching, then, would speak to all three conversations:

The conversation between gospel and culture — Preaching embodies and explains the relevance and the challenge of the gospel to secular culture.

The conversation between gospel and church — Preaching explores the ways the gospel transforms God’s people.

The conversation between church and culture — Preaching calls the church to live in this gospel transformation so that its way of living in the world becomes the substance of its conversation with the culture.

All of this is a tall order for a sermon – and still somewhat nebulous. We need still a clearer path, and more manageable handles for culture-shaping proclamation. In the next post in this series, we will continue our quest by looking at the contribution of Andy Crouch to this conversation.